When I

think back to highlights from my music career,

many performances with the Royal Philharmonic

Orchestra around England and in London's Royal

Festival Hall, and a "live" TV recording with

Luciano Pavarotti in front of an audience of

25,000, are high on the list.

I was born

and raised near a large city in Sweden, growing

up in a community which, luckily, had a

wonderful music school, available to children

from an early age. Hence, from the age of 10 I

took drum lessons at the local music school.

After high school, I did my military service in

the Swedish cavalry and when completed, moved on

my own to London, studied with famous English

percussionists, (notably James Blades the

‘Father’ of British percussion and Mike Skinner,

principal percussion in the Covent Garden Opera

Orchestra) and in 1976 was admitted to the Royal

Academy of Music (RAM) in London, where I

studied until 1980.

I have

worked as a freelance musician with major

English orchestras such as the Royal

Philharmonic Orchestra, Sadler's Wells Royal

Ballet Orchestra, and the Covent Garden Opera

Orchestra, among others. I have taught in

schools in Germany and at the College of Music,

University of Cape Town, South

Africa. I worked

as principal percussionist at the Cape Town

Opera for 10 years where I was also orchestra

director for a couple of years.

After 12

years in South Africa, my wife and I moved our

family to the United States where I found a job

in the IT industry, working as, among other

things, project manager for various IT projects

for 19 years. During these years I continued to

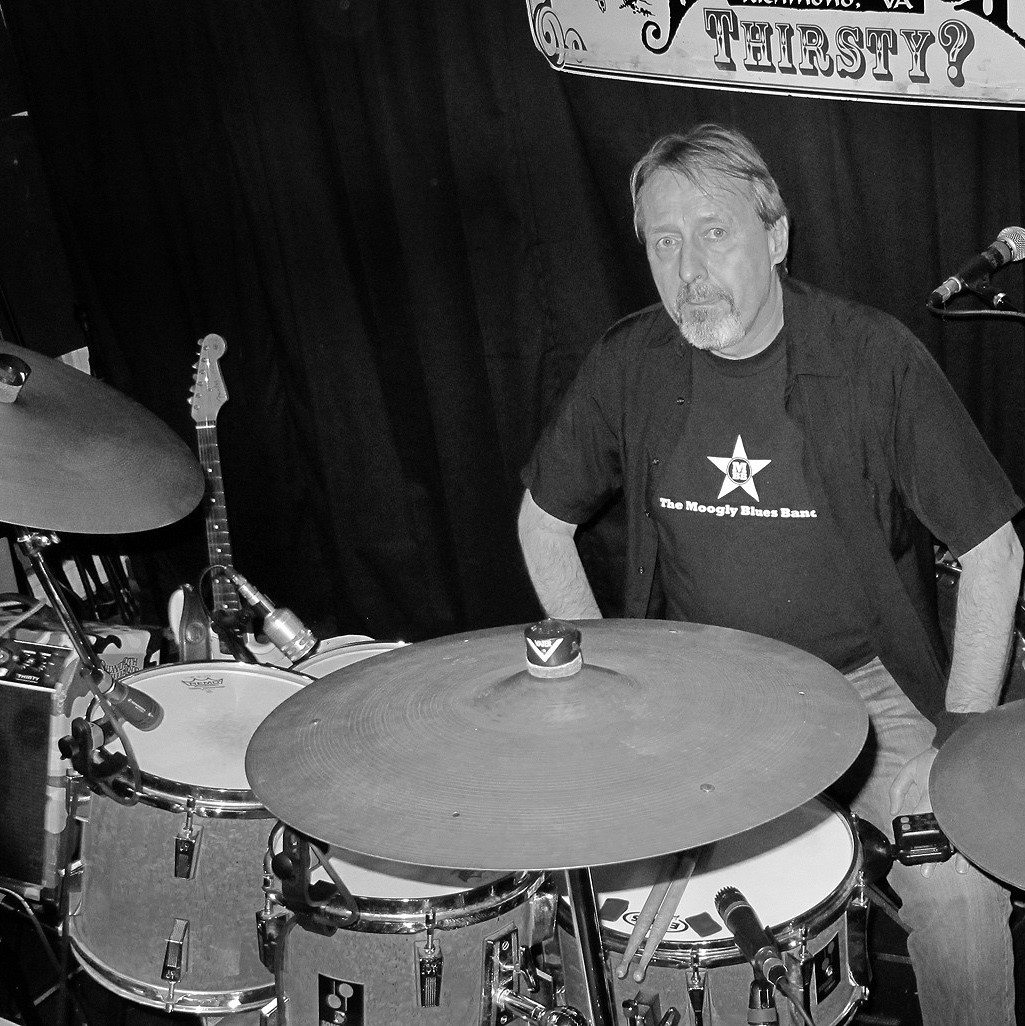

be active in the music field, playing

drums in a blues band and leading my own jazz

quartet on the vibraphone.

My experiences in the IT field, coupled with

daily use of technology, has facilitated my

understanding and use of technological aids

such as apps and digital tools to enhance my

instrumental practice.

After more

than 50 years as a musician I still practice as

much as possible, between 3–5 hours per day, and

have since 2020 conducted individual research in

the field of music pedagogy, with a special

focus on how musicians work to

build up their expertise. Additionally, since

2019 I have been collecting biometric data

during my own practice, using different data

collection devices to identify moments of stress

during practice; these are described

later in this blog.

Challenging

myself

“Si l’on se

préoccupait de l’achèvement des choses, on

n’entreprendrai jamais rien”

If we were

concerned about the completion of things, we

would never undertake anything

~ Francis I, King of

France, on the building of Chateau

Chambord

Many

studies show the positive effects on

people's health from singing and music

making in communal settings and

learning a musical instrument. Such

effects manifest themselves in

relaxation, increased blood movement,

deeper breathing and activation of the

internal muscles of the body and the

brain (Magrini, 2019). To make music

together with others adds to the

communication and social interaction,

giving a sense of community with other

musicians and provides extraordinary

physiological benefits (Tsugawa,

2009; Balbag et al, 2014; Daykin et

al, 2014; Yesil & Ünal,

2017; Helton, 2019; Barbeau &

Cosette, 2019).

A

study at the Royal College of Music,

London, UK, explores the practice habits

of students at music conservatories

(Taylor, 2019). Another explores results

from a practicing workshop in a music

academy (Johansen and Nielsen,

2019). No study, to the best of

my knowledge, has focused

exclusively on the individual mature

(50+) musician and possible health and

well-being benefits derived from individual instrumental

practice.

The

individual musician spends many hours

alone on individual practice of his

instrument or voice. This can often be

both physically and mentally demanding.

Of great concern is that research over

the past 30 years reveals alarming rates

of injury and unacceptably high levels

of performance related health issues

among musicians of all ages (Wijsman

& Ackerman, 2018).

Though

correlational and experimental studies showing

the role instrumental practice has on slowing

the natural decline of cognitive facilities

have been conducted on individual musicians

(Roman-Caballero et al, 2018), studies of the

individual musician are few and needed

(Lehmann, 2014, p. 181). A study by

Talbot-Honeck and Orlick (1999), limited to

classical musicians from a younger age group

examined, inter alia, practice routines.

However, no study has focused on the older

musician sitting alone in his room during long

practice sessions and especially on how the

perceived general health and well-being of the

musician is affected by such a disciplined

regime.

I base my

personal practicing activities on the goal of at

least 1% improvement every day, and, in the early

part of 2019 set myself a set of challenges as

part of my daily drum practice regimen.